BepiColombo Project

The ESA/JAXA BepiColombo project has made the third of six flybys of Mercury to help it reach orbit around the planet in 2025. During this flyby, it took pictures of a newly named impact crater and tectonic and volcanic features.

The closest approach happened at 19:34 UTC (21:34 CEST) on June 19, 2023, on the planet’s night side, about 236 km above the surface.

“The flyby went very well, and images from the monitoring cameras taken during the close approach phase of the flyby have been sent to Earth,” says Ignacio Clerigo, who is in charge of the BepiColombo spacecraft’s operations for ESA.

“The next Mercury pass won’t happen until September 2024, but problems will still be solved before then. Our next long solar electric propulsion “thruster arc” is set to begin in early August and last until mid-September. Together with the flybys, the rocket arcs are a key part of helping BepiColombo slow down against the strong pull of the Sun’s gravity before it can enter orbit around Mercury.

Geological curiosities

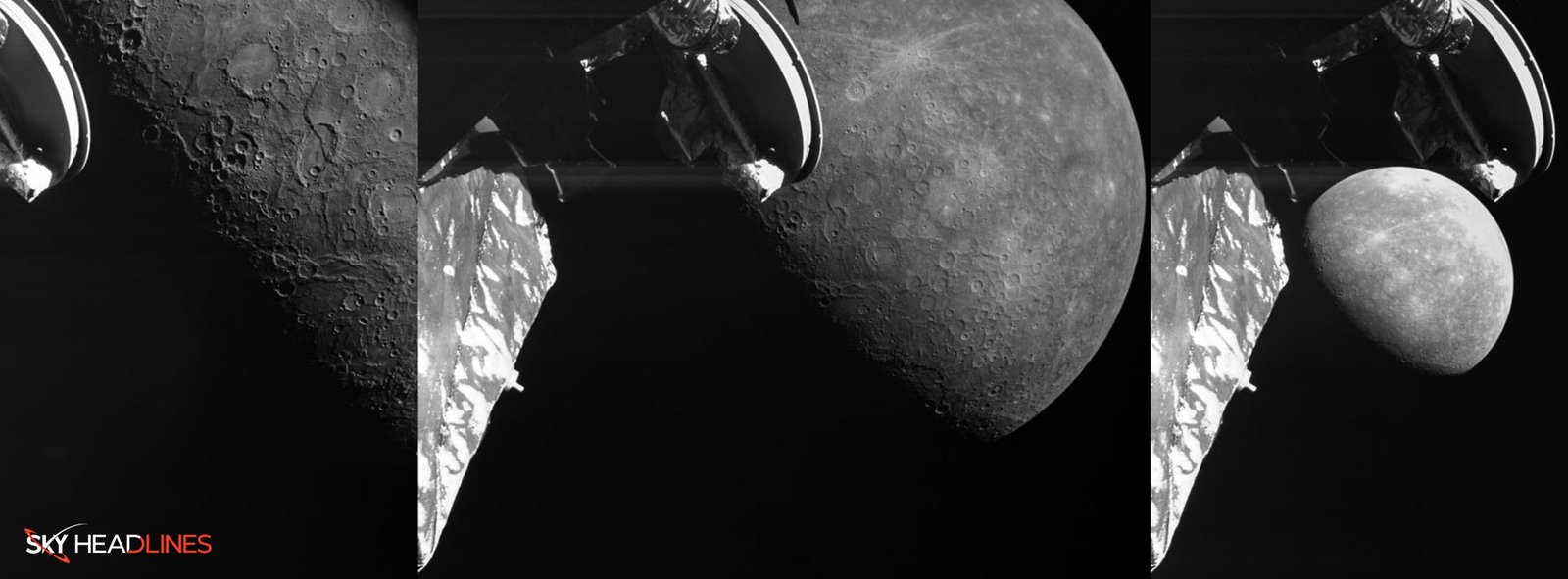

Monitoring camera 3 took dozens of pictures of the hard planet during last night’s close pass. The black-and-white pictures with a size of 1024 x 1024 pixels were downloaded overnight and early this morning. Here are three photos that were released early.

As BepiColombo got closer to the planet on its night side, a few features started coming out of the shadows about 12 minutes after the closest approach, about 1800 km from the surface. From about 20 minutes after the closest approach and on, when the spacecraft was about 3500 km away, and further, the planet’s surface was better lit for taking pictures. Many natural features, including a newly named crater, can be seen in these close-up pictures.

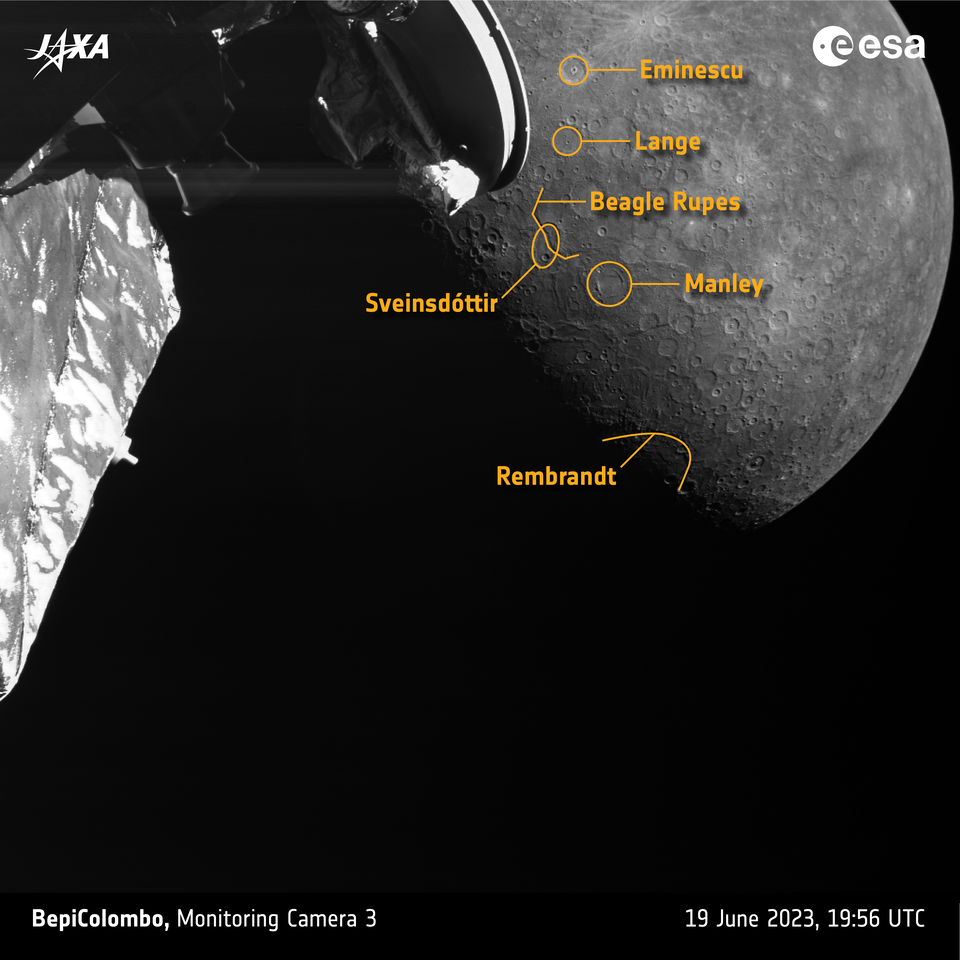

Edna Manley in BepiColombo

Artist Edna Manley’s name is on a crater. The International Astronomical Union’s Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature has just named a 218 km-wide peak-ring impact crater “Manley” after Jamaican artist Edna Manley (1900–1987). The crater can be seen just below and to the right of the antenna in the two closest images.

“When we were planning the images for the flyby, we knew this big crater would be visible, but it didn’t have a name yet,” says David Rothery, Professor of Planetary Geosciences at the Open University in the UK and a part of the BepiColombo MCAM imaging team. “It is clear that BepiColombo scientists will be interested in it in the future because it has dug up dark “low reflectivity material” that may be left over from Mercury’s early carbon-rich crust. Also, the pond floor inside has been filled with smooth lava, which shows that Mercury has been volcanically active for a long time.

Even though it needs to be clarified from these flyby pictures, BepiColombo will learn more about what makes the dark stuff around Manley Crater and elsewhere. To learn more about Mercury’s natural past, it will try to figure out how much carbon it has and what minerals are near it.

Snaking scarps

In the two closest pictures, near the planet’s terminator and to the right of the spacecraft’s antenna, you can see one of the planet’s most impressive geological push systems. The Beagle Rupes cliff is an example of one of Mercury’s many lobate scarps, which are tectonic features that probably formed when the planet cooled and contracted, making its surface twisted like an apple left out in the Sun too long.

In January 2008, when the NASA Messenger mission flew by the planet for the first time, it was the first time anyone saw Beagle Rupes. It is about 600 km long and goes through a crater called Sveinsdóttir, which is long and narrow.

Beagle Rupes is on the edge of a piece of Mercury’s crust that has been pushed at least 2 km to the west. Each end of the scarp curves back more than most other scarps on Mercury.

Also, many nearby impact basins have been filled by volcano lava, which makes this an interesting area for BepiColombo to study again.

The complex landscape is shown well by how the shadows are stronger near the line between day and night. This gives a sense of the heights and depths of the different features.

The BepiColombo image team members are already having a lively discussion about how volcanism and tectonics affect this area.

Valentina Galluzzi of Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) says, “This is a great place to study Mercury’s tectonic history.” “The way these escarpments interact with each other shows that as the planet cooled and shrunk, it caused the surface crust to slip and slide, making several strange features that we will study more closely once we are in orbit.”

BepiColombo Farewell ‘Hugs’

As BepiColombo moved away from the planet, it looked like it fit between the spacecraft’s antenna and body, as seen in these pictures. As BepiColombo moved away from Mercury, it also took a series of “goodbye Mercury” pictures, which will be sent to Earth tonight.

In addition to taking pictures, some scientific instruments were turned on and used during the flyby. These instruments measured the magnetic, plasma, and particle environments around the ship from places that aren’t usually reachable during an orbital journey.

“Mercury’s heavily cratered surface shows that asteroids and comets have hit it for 4.6 billion years,” says ESA research fellow and planetary scientist Jack Wright, also a BepiColombo MCAM imaging team member. “This, along with the planet’s unique tectonic and volcanic features, will help scientists figure out where the planet fits in the history of the Solar System.”

“The pictures taken during this pass, which were the best MCAM has ever taken, set the stage for BepiColombo’s next exciting mission. With the full suite of scientific tools, we will study everything about Mercury, from its core to its surface processes, magnetic field, and exosphere, to learn more about how a planet close to its parent star came to be and how it changed over time.

BepiColombo Passing Mercury

The next time BepiColombo will pass by Mercury will be September 5, 2024, but the teams have plenty to do until then. Soon, the mission will enter a very difficult part of its journey. To keep stopping against the Sun’s huge gravity pull, solar electric propulsion will gradually increase through extra propulsion times called “thrust arcs.” These thrust arcs can last anywhere from a few days to two months. The longer arcs are broken up occasionally to improve guidance and maneuvering.

Beginning of Next Story Arc

The next story arc will begin at the beginning of August and go on for about six weeks.

Santa Martinez Sanmartin, the mission manager for ESA’s BepiColombo, says, “We are already working hard to get ready for this long thruster arc. We are increasing communications and commanding opportunities between the spacecraft and ground stations to make sure that thruster outages don’t happen too often during each sequence.”

“This will become more important as we move into the final stage of the cruise phase because the frequency and length of the thrust arcs will increase significantly. By 2025, they will be happening almost constantly, and it will be very important to stay on course as well as possible.”

BepiColombo Using Solar Power

Throughout its lifetime, BepiColombo Mercury Transfer Module will use solar electric power for over 15,000 hours. This and the spacecraft’s nine flybys of planets (one at Earth, two at Venus, and six at Mercury) will get it into orbit around Mercury. The modules of the ESA-led Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the JAXA-led Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter will go into different orbits around the planet that complement each other. Their major research mission will start in early 2026.