NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has been helping scientists make giant strides in understanding where all that cosmic dust production in early galaxies from.

Exploring Supernovae and dust production

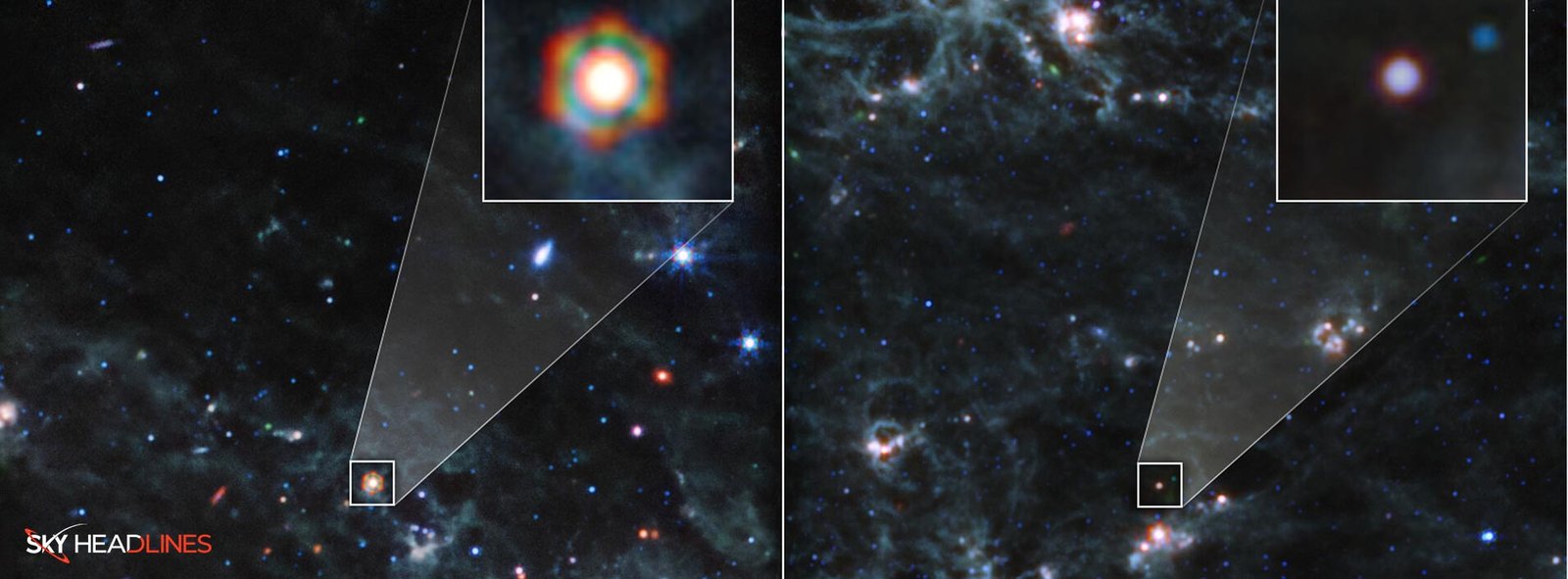

They’ve been closely watching two major star explosions, Supernova 2004et (SN 2004et) and Supernova 2017eaw (SN 2017eaw). What’s exciting is that they came to know about a lot of dust production within the remnants of these explosions. This discovery supports the idea that these massive star explosions, or supernovae, could have been the main dust-makers in the young universe.

You might think dust is trivial, but it’s a massive deal in the cosmos, especially for creating planets. When a star goes kaput, the dust production by it into space carries the raw materials needed to birth new stars and planets. For years, astronomers have been scratching their heads over where all this dust originates.

Supernovae could be the big reveal in this cosmic mystery. When a star on its last legs goes boom, it releases a gas that spreads and cools down, resulting in dust production.

“We’ve known this was a possibility, but we didn’t have much hard proof,”

says Melissa Shahbandeh from Johns Hopkins University and the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, Maryland.

“We’ve been able to study the dust from just one supernova that’s pretty close to us, Supernova 1987A, which is 170,000 light-years away. When the gas from these explosions cools enough for dust production, you can only spot it with sensitive equipment and at certain wavelengths.”

Revealing far-off Supernovae

But what about supernovae that are farther off, like SN 2004et and SN 2017eaw, located in a galaxy called NGC 6946, some 22 million light-years away? The answer lies in Webb’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument). It’s the only powerful tool to capture a wide range of wavelengths with high sensitivity for these distant supernovae.

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope found new dust in SN 1987A about ten years ago. But the images from Webb mark the first significant leap in understanding how supernovae create dust. And boy, did they find dust and lots of it! Researchers discovered over 5,000 Earth masses worth of dust in SN 2004et.

“We’re seeing dust volumes in SN 2004et comparable to what we saw in SN 1987A, even though it’s way younger,”

explains program leader Ori Fox from the Space Telescope Science Institute.

“It’s the largest dust haul we’ve discovered in a supernova since SN 1987A.”

Astronomers have spotted young galaxies filled with dust, yet they are too young for medium-sized stars like our Sun to have this much dust production as they aged. This suggests that bigger, shorter-lived stars could have created so much dust by dying off rapidly and in large numbers.

Dust production in SN 2004et

We know that supernovae is responsible for dust production, but scientists needed to determine if the dust could withstand the shock waves produced within the star following the explosion. The substantial amount of dust spotted in SN 2004et and SN 2017eaw implies that the dust can survive the violent blast, confirming that supernovae are critical players in dust production.

The researchers also hinted that their current dust mass estimates might only be a glimpse of the whole picture. Thanks to Webb, they can now detect even colder dust. However, even harder dust might be hidden underneath the surface layers, which only gives off radiation at even further wavelengths.

The team emphasizes that these findings are just a sneak peek of what we can learn about supernovae and their progenitor stars by studying their dust production.

“People are getting super excited to find out what this dust can tell us about the heart of the star that exploded,”

Fox notes.

“Once they see our findings regarding dust production, I’m sure other scientists will develop new ideas for studying these dusty supernovae.”

The two supernovae, SN2004et and SN2017eaw, are the first pair of five this project studies. The observations were made as part of Webb General Observer program 2666, and the findings regarding dust production were published on July 5 in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.