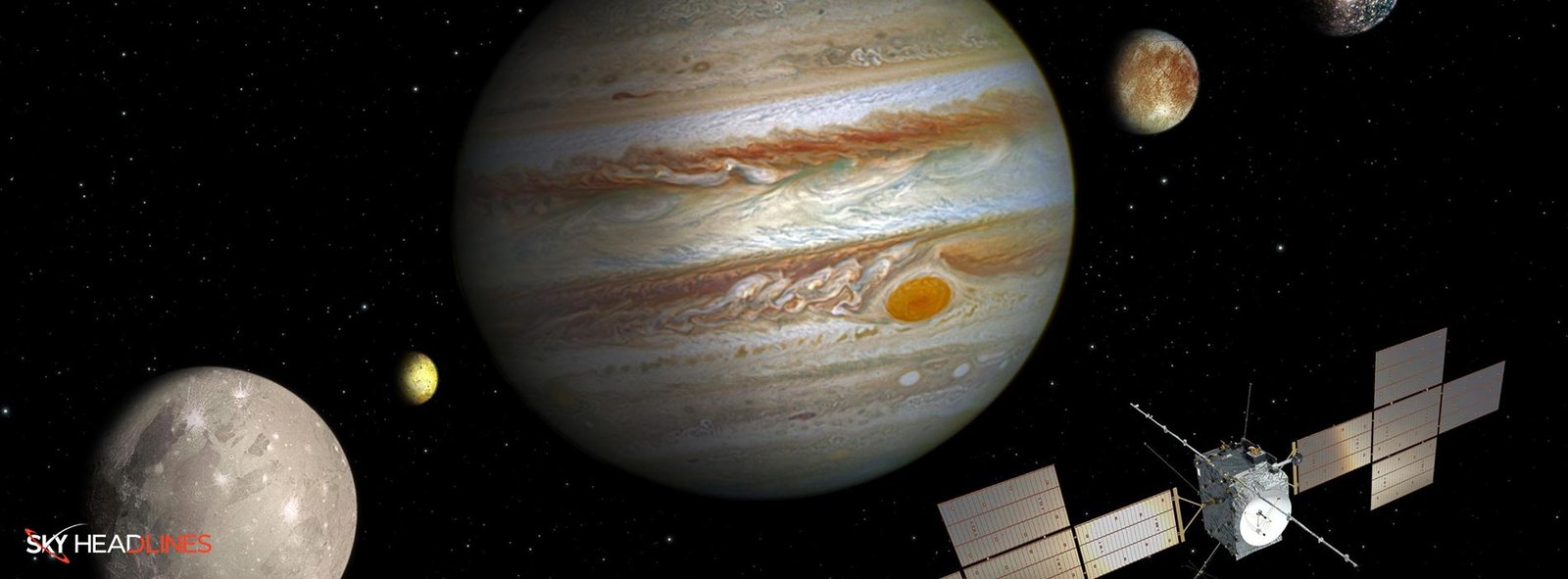

Before launch, the stakes were tremendous. Airbus designed Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) to study Jupiter’s icy moons.

What is the significance of RIME in the JUICE inquiry?

Jupiter Icy Moon’s Explorer (RIME) antenna, one of eleven research equipment, is crucial to that inquiry. RIME will remotely study Jupiter’s ice moons’ sub-surfaces. Its radar waves will penetrate the moons to 9 km and expose 50–140 m details. This will help them comprehend their geology and habitability.

To collect this data, scientists had to fold up some hardware to launch the spacecraft and its equipment into orbit.

The Ariane 5 rocket that launched Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer could not contain the RIME antenna, which was 16 m long. Thus, it had two booms of four segments each. Three of the eight pieces would deploy on one side of the spaceship, three on the other, and two would stay put. During the launch, two brackets held the three deployable portions onto the fixed section.

How does the problem of a stuck pin occur in the RIME antenna?

ESOC, Darmstadt, Germany, would remotely trigger non-explosive actuators (NEAs) in space. Each NEA removed a bracket pin to spring its part into position. Problems started there. ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer Senior Mechanisms Engineer and its team member Ronan Le Letty advised the flight control team at ESOC during the RIME deployment.

Three days after the launch, the process of ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer began.

What was the process of Jupiter’s Icy Moons Explorer?

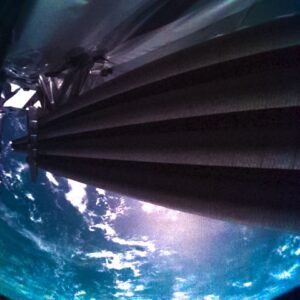

As usual, the first step went smoothly. Two spacecraft-mounted cameras tracked RIME deployment. The antenna portion was visible in some downloads but not in others. The NEA fired, the pin released, and the antenna section snapped between photos. The external camera and telemetry data showed the team in place. The abrupt boom deployment caused the spacecraft to oscillate, and the Attitude and Orbit Control System (AOCS) corrected for the final of these movements.

The crew moved on to the second part of Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, satisfied.

Fire the actuator. Telemetry was received before photographs, but something was awry. It was not oscillating. The camera image returned seconds later. The stowed boom portion was visible. Deployment failed.

“The most unwanted situation is happening,” adds Ronan. Two, three, four times, we checked the photo. We activated the actuator again, but nothing happened.”

Toulouse-based Airbus Defence and Space watched in bewilderment. They were the spacecraft’s leading contractor in 2015 and oversaw its design, construction, and testing.

“We knew that we had to quickly try to understand what had happened and then try to find a workaround,”

says the head of ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, engineer Frédéric Faye.

After overcoming their amazement, the teams had a teleconference the following day to discuss the oddity. They had to remove the stuck part, but they couldn’t do anything that might risk the deployment of the other segments or the spaceship.

How did the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer team overcome the mentioned issue?

The teams first considered ice on the pin holding the portion. Spacecraft depart Earth in chilly, airless conditions. The craft’s material will release a small amount of water vapor due to the abrupt air pressure drop. The spacecraft’s cold surfaces can freeze this.

Rotating the spacecraft so the antenna faces the Sun would remove the ice since RIME has no heaters. However, RIME’s spacecraft’s “cold face” was never meant to be exposed to direct sunlight after launch. Nor were its parts, instruments, and systems.

After days of observation, the crew slowly slew the spacecraft to light the surface.

“We illuminated the RIME bracket with eight slews over two weeks,”

explains ESOC Spacecraft Operations Manager Angela Dietz. They watched the onboard sensor telemetry each time they

exposed the surface for longer to determine its limitations. The initial maneuver lasted 25 minutes. They eventually felt safe exposing the surface for 73 minutes. Other recovery possibilities were also considered in Esa’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer. If RIME were not frozen and the pin had just stuck, moving the spaceship may loosen it, but “shaking” is too strong a term.

The thrusters may gently shake the six-tonne spaceship. However, the teams decided to attempt. The teams had to be careful when relocating the trapped pin. They couldn’t risk a powerful spaceship jolt injuring others. As with the heater, they cautiously tested this move.

Angela explained:

“We fired thrusters and used the main engine, often with heating slews. The thrusters were even fired in a certain sequence to shake off the stacked boom, but we only saw small movements within the bracket,”

So the team tried various options.

Mechanical stress and heating as recovery measures in JUICE

German antenna maker SpaceTech presented a recovery solution. It meant installing the other four antenna components as usual. They realized that each NEA would cause a slight mechanical stress in the antenna, which may free the pin.

Then, the manufacturer succeeded. SpaceTech experts reproduced the phenomenon using a replica of the antenna used for testing and found that the nearest NEA generally dislodged the trapped pin. The antenna should be heated by sunshine to improve results.

The flying model had not been tested at space temperatures, but the engineering model had. The scientists decided that the icy circumstances during the unsuccessful NEA release may have contributed. Thus, the Sun should warm the antenna before any subsequent actions to make it as close to “room temperature” as where it functioned.

What strategies were considered to retrieve the instrument?

The teams of JUICE met to discuss how to retrieve the instrument after coming up with many proposals. At a SpaceTech technical workshop, the teams tried heating first. If they failed, they would fire the other NEAs after warming them with sunshine. Ronan feels this exercise in writing a plan and having all the teams working toward it was helpful.

The pressure was rising many weeks after the incident. As vital as RIME is, the mission had a timeline. Guillaume Chambon of Airbus’s Technical Authority Team calls this the most complex part of the recovery. Guillaume oversaw Airbus’ recovery.

“You have to act fast because everyone is expecting you to make progress, but you need to take enough time to consider all the side effects of what you are proposing,”

He also added:

Guillaume realized an issue one afternoon while planning the rescue effort. If they are deployed, usually, two antenna segments may clash.

The possible threat in deploying regular RIME antenna for Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer

RIME has six deploying parts, three on each side of the spaceship. In the typical deployment scenario, an NEA is fired on one antenna side and then the other. If they performed this now and the trapped piece released, the antenna’s two sides would deploy in opposite directions and smash.

The teams reordered deployment and began recovery. The antenna stayed stationary while the spacecraft was heated to remove ice. Thus, the only way to rescue the antenna was to heat it again and continue the deployment, hoping the shocks from the other NEAs would unjam the pin. But each NEA could only be fired once. It was all-or-nothing.

Teams started this last effort at 2 pm on 12 May at their consoles. After sending the command, the teams checked the data for a successful oscillation. The spaceship moved. Was it right? Have they dislodged the stuck segment?

The camera image revealed everything—total success. We deployed the antenna’s three parts. Angela believes the operations staff got quietly confident.

The task wasn’t-still needed to be completed. They were halfway through deployment. RIME required one more NEA to deploy the second boom before it could operate. Since the crew understood that the pins might clog, some felt more strain. The last nail was the most important. If any prior ones jammed, the team might have fired the next in succession and hoped the shock would finish the job, as it did on the first stuck part. No more NEAs may be fired. If the pin jammed, they may lose at the end.

What was the all-or-Nothing approach in the JUICE’s RIME antenna recovery?

At this time, Airbus JUICE project manager Cyril Cavel thought about the scientists who relied on them. Some worked on the antenna for decades. These folks received RIME industrially. The radar experiment would only succeed with this antenna. He believes that would be worse than a disgrace.

Indeed, present planetary scientists may have lost the chance to properly grasp what existed beneath those lovely moons’ ice surfaces.

“We knew that even though the RIME was one instrument out of ten, a failure to open the antenna fully would have degraded the scientific performance of the mission and compromised the – until that moment – the excellent image of Juice and ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer to the external world,”

ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer Project’s Manager, Giuseppe Sarri, said:

The crew took one last measure. The previous bracket had been in sunlight for a maximum of 73 minutes that day. Its temperature was greater than that of the German laboratories. The crew rotated the spacecraft, shifting the antenna away from the Sun, then waited three to four hours for its temperature to decrease to replicate that lab.

Successful completion of deployment in the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer mission

Frédéric believes the three-to-four hours were lengthy. After waiting, the command was given. The NEA triggered, Juice oscillated, and the AOCS stabilized the ship. Finally, the cameras showed RIME wholly deployed. Ronan was relieved yet disbelieving at the deployment. It was like the incident’s first day. Four weeks of intense strain were suddenly gone, causing a surprise.

“Despite the pictures, I couldn’t believe it,”

He added:

“When RIME was eventually released, I could almost see tears in my colleagues,” recalls Giuseppe, “But we were positive from the beginning, and the Champagne was already in the fridge…”

After the bubbly was sipped and the team slept, the flight controllers at ESOC completed all spacecraft deployments. The RIME anomaly teams at ESA, Airbus, and SpaceTech are finishing their analysis of the original cause to prevent it in comparable systems.