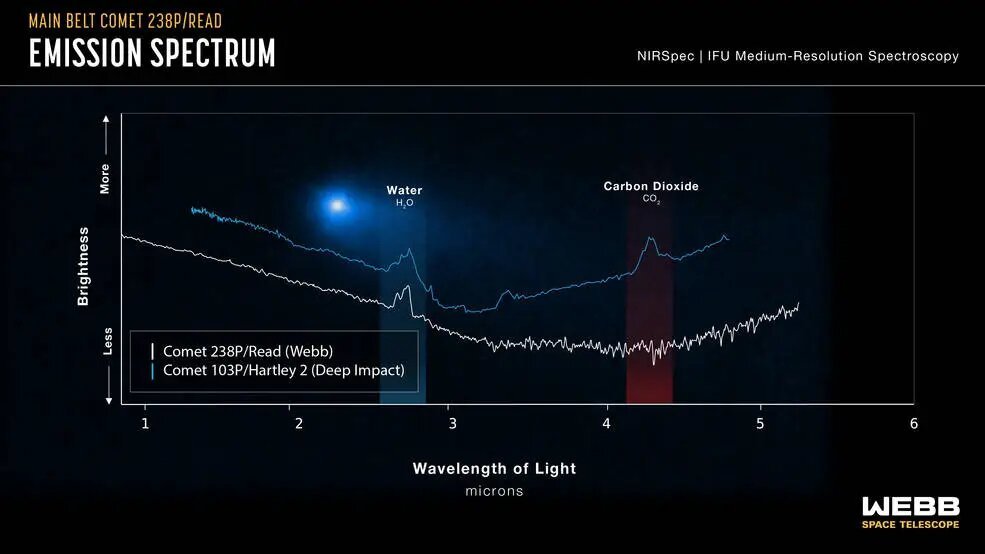

Another long-awaited scientific breakthrough has been made possible by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, this time for solar system scientists investigating the origins of Earth’s copious water. Astronomers have detected gas – especially water vapor – near a comet in the main asteroid belt for the first time using Webb’s NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph), indicating that water ice from the early solar system can be retained in that region. The effective identification of water, however, introduces a fresh puzzle: unlike other Main Belt comets, Comet 238P/Read did not emit measurable carbon dioxide.

“Our water-soaked world, teeming with life and unique in the universe as far as we know, is something of a mystery – we’re not sure how all this water got here,” said Stefanie Milam, Webb deputy project scientist for planetary science and co-author on the research that reported the discovery. “Understanding the history of water distribution in the solar system will help us understand other planetary systems and whether they might be on their way to hosting an Earth-like planet,” she adds.

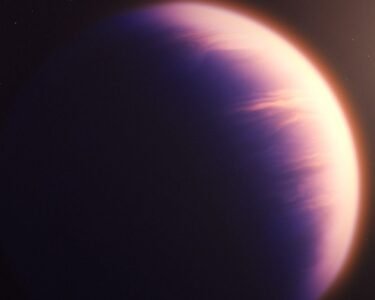

Comet Read is a main belt comet, which is an object that lives in the main asteroid belt but has a halo, or coma, and tail like a comet. Comet Read was one of the first three comets used to establish the category of main belt comets, which is a relatively new classification. Previously, comets were thought to live in the Kuiper Belt and Oort Cloud, beyond Neptune’s orbit, where their ice might be kept away from the Sun. Comets get their unique coma and flowing tail from frozen ice that vaporizes as they approach the Sun, which distinguishes them from asteroids. Scientists have long suspected that water ice could be retained in the warmer asteroid belt, within Jupiter’s orbit.

But, until Webb, definitive proof remained elusive.

“In the past, we’ve seen objects in the main belt with all the characteristics of comets, but only with this precise spectral data from Webb can we say yes, it’s definitely water ice that’s creating that effect,” said University of Maryland astronomer Michael Kelley, the study’s lead author.

“With Webb’s observations of Comet Read, we can now demonstrate that water ice from the early solar system can be preserved in the asteroid belt,” Kelley explained.

The absence of carbon dioxide came as a bigger surprise. Carbon dioxide typically accounts for around 10% of the volatile material in a comet that can be easily evaporated by the Sun’s heat. The scientists propose two possibilities for the lack of carbon dioxide. Comet Read may have possessed carbon dioxide when it formed, but it has since lost it due to heated temperatures.

“Being in the asteroid belt for a long time could do it – carbon dioxide vaporizes more easily than water ice, and it could percolate out over billions of years,” Kelley speculated. He also speculated that Comet Read could have formed in a particularly heated region of the solar system where no carbon dioxide was accessible.

According to scientist Heidi Hammel of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), lead for Webb’s Guaranteed Time Observations for Solar System Objects and co-author of the study, the next step is to expand the research beyond Comet Read to see how other main belt comets compare. “These asteroid belt objects are small and faint, but thanks to Webb, we can finally see what’s going on with them and draw some conclusions.” Do other main belt comets lack carbon dioxide as well? “It will be exciting to find out in either case,” Hammel remarked.

Milam, a co-author, envisions bringing the research even closer to home. “Now that Webb has proved that water has been retained as close to the asteroid belt as possible, It would be fascinating to follow up on this discovery with a sample collecting mission to see what else the main belt comets have to teach us.”